Australasian bittern/matuku

The endangered matuku inhabits wetlands throughout New Zealand. DOC is focusing on developing methods for surveying bittern systematically and for restoring wetlands.

Source:

DOC

Bitterns are extremely cryptic and rarely seen. This is due to their secretive behaviour, inconspicuous plumage and the inaccessibility of their habitat. Their presence is most commonly discerned through hearing the distinctive ‘booming’ call of the males during the breeding season. Bittern occasionally show themselves in the open along wetland edges, dykes, drains, flooded paddocks or roadsides, often adopting their infamous ‘freeze’ stance, with the bill pointing skyward, even when caught out in the open.

Source:

NZ birds online

âRead more about the matuku and its importance, both ecologically and culturally, here and here.

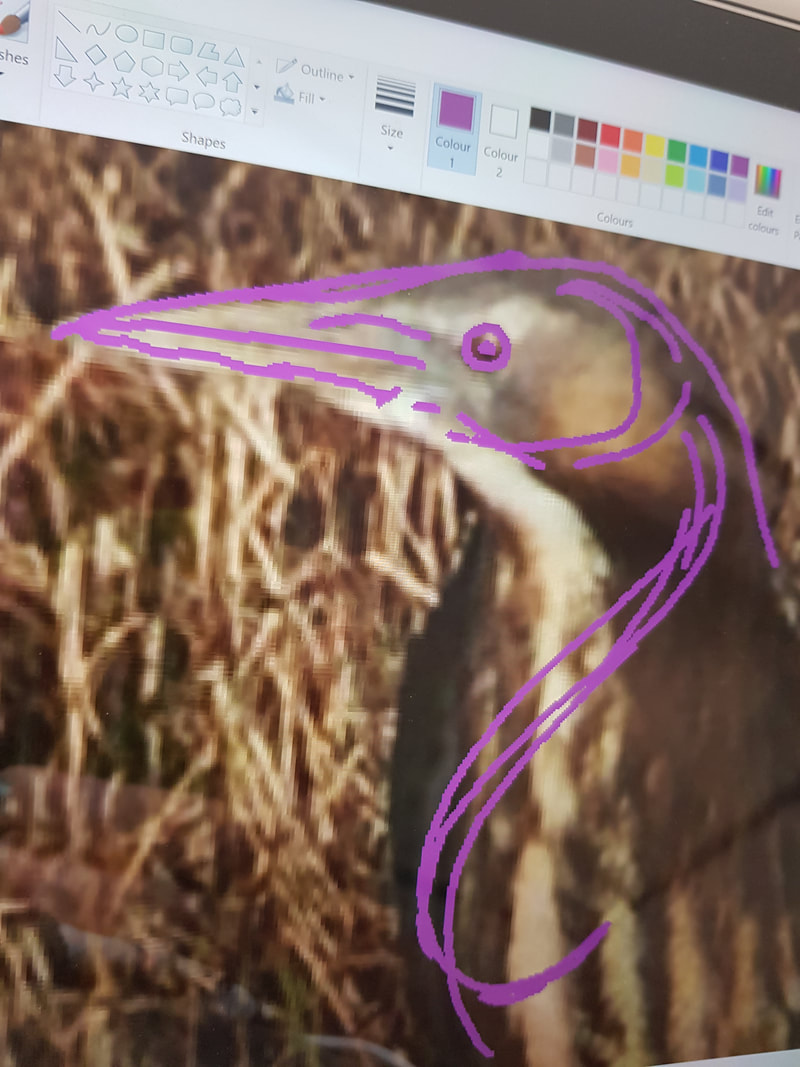

A bittern in the “freeze” stance. Of course I have to draw this pose. Image © imogenwarrenphotography.net by Imogen Warren

|

A matuku chilling by the pond. Image © Noel Knight by Noel Knight

|

Sources and resources

As always, when trying to get to know subjects like rare native birds, I have to lean on online resources for information on what they look like and how they move. As usual for this series, my main sources are:

The Bittern Conservation – New Zealand Facebook page (follow it! help amplify their message!) has this lovely video of bitterns “booming” – it sounds a little bit like that sound you make when you blow into a glass bottle (not the cows lowing). Several of the other photos used for reference here are also from their page – I embed the code or link to the page wherever I can, so you can click straight through to the source.

What is going on with that neck, though?

When I draw something, I need to know how exactly it fits together, even though I only end up drawing what I can actualy see. This is particularly important with my

ligne claire style, as there’s no room for shading or additional pencil lines to help give a sense of depth – it’s all about choosing the perfect line to convey the shape of the subject.

When I draw plants, I take lots of photos, but I also move the plant around, and really look at how everything joins to everything else.

âThat kind of manipulation is not something your average rare bird will tolerate. So for animals, I go to their anatomy, and try to see how it aligns with the photos I can see.

âBut what is the deal with all that neck situation??

I was thrilled to discover

this blog post by Emily Willoughby after finding the above image via Google. The work of a self-described “

paleoartist” is precisely what I need to help me understand this bizarre phenomenon.

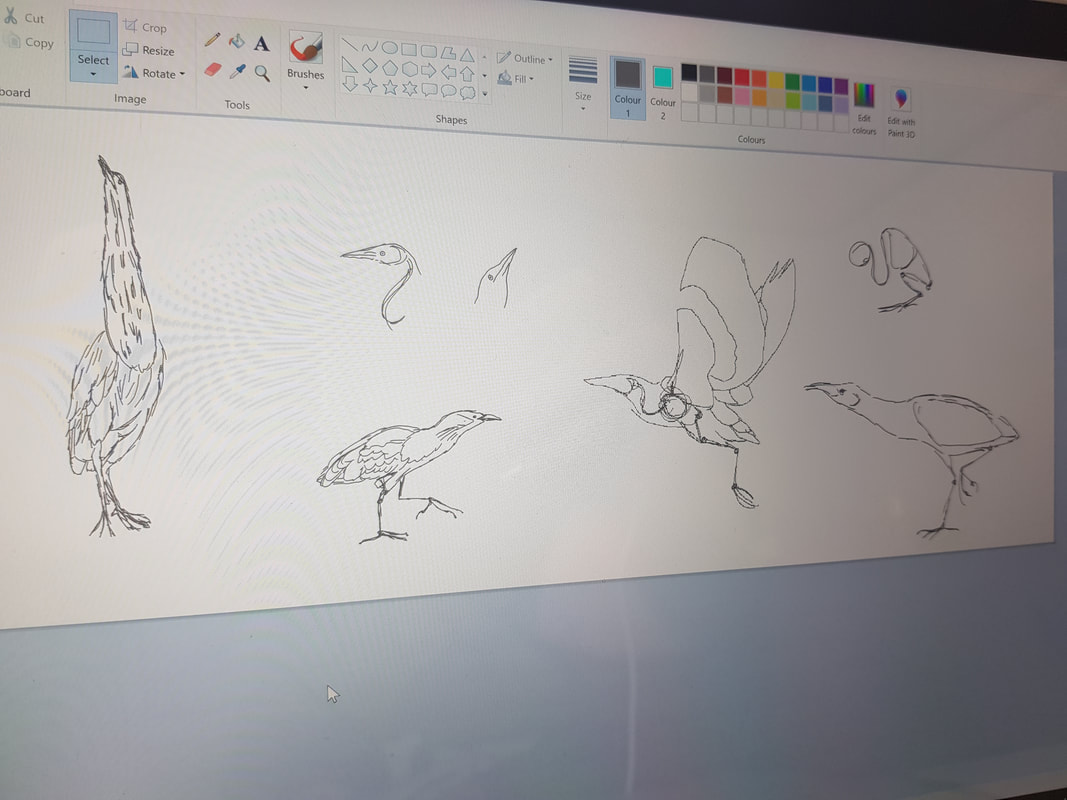

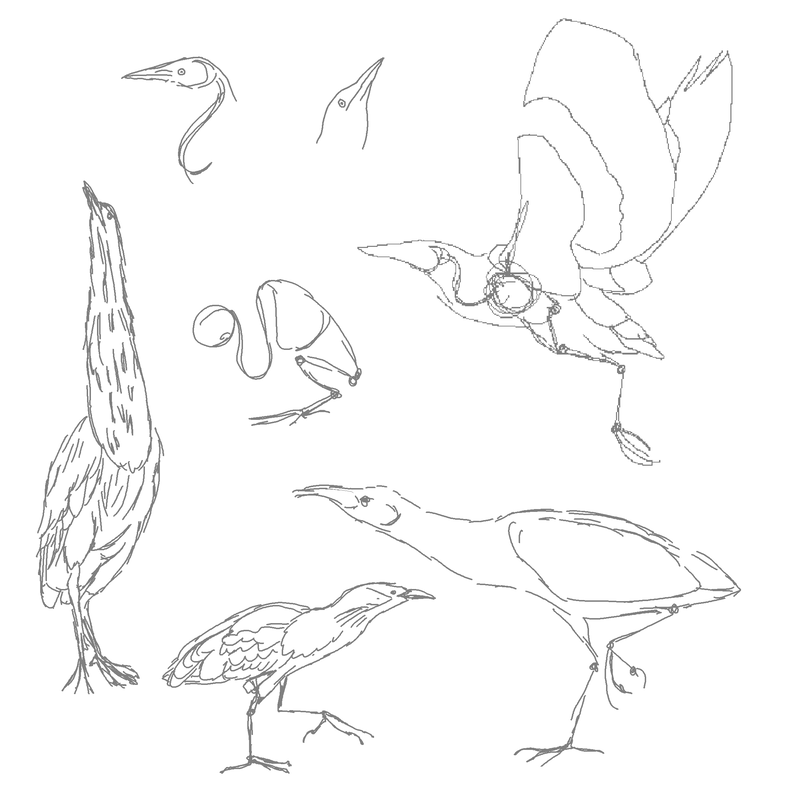

Initial sketches

It’s really helpful to use the photos to understand how the underlying body functions, so that when I get to the drawings, they look like they articulate correctly. For example, not many of the photos show the feet, but I know how they work, so I can add them in. I can also change the angle of the head, the exact attitude of the wings, etc.

Speaking of the wings, that’s the other thing that I am working through – how the feathers work and what level of detail I need to show to convey the changes in colouring, without losing the simplicity of the design.

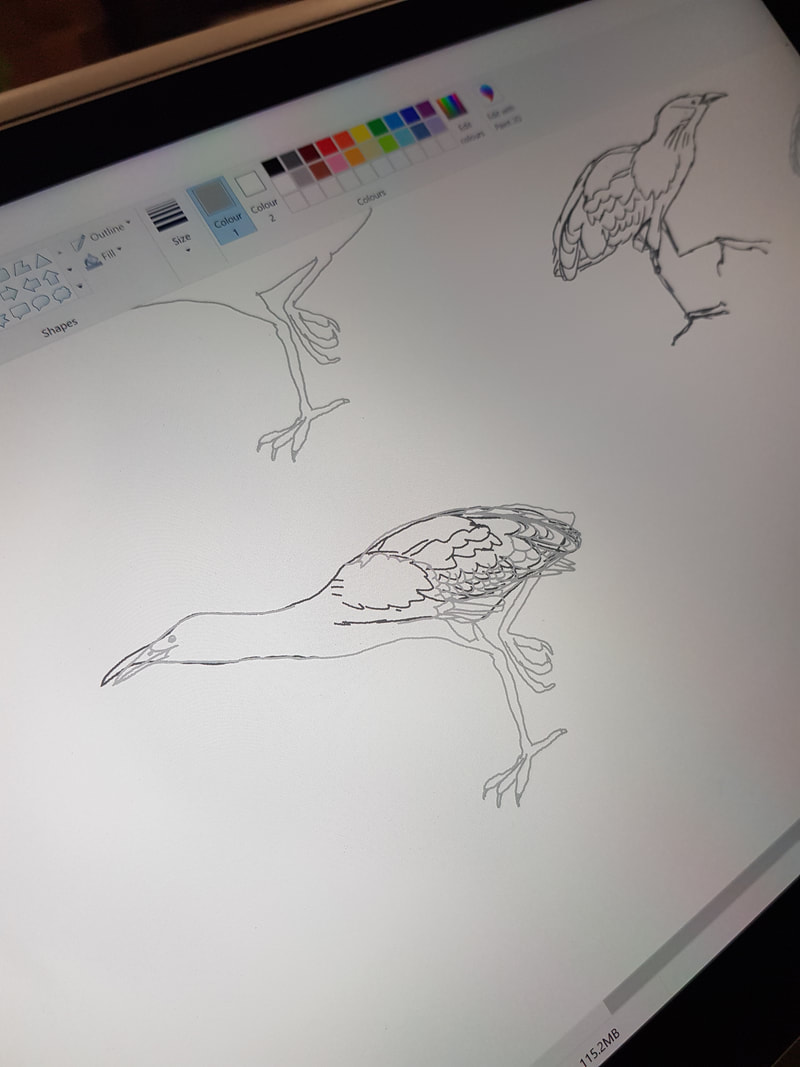

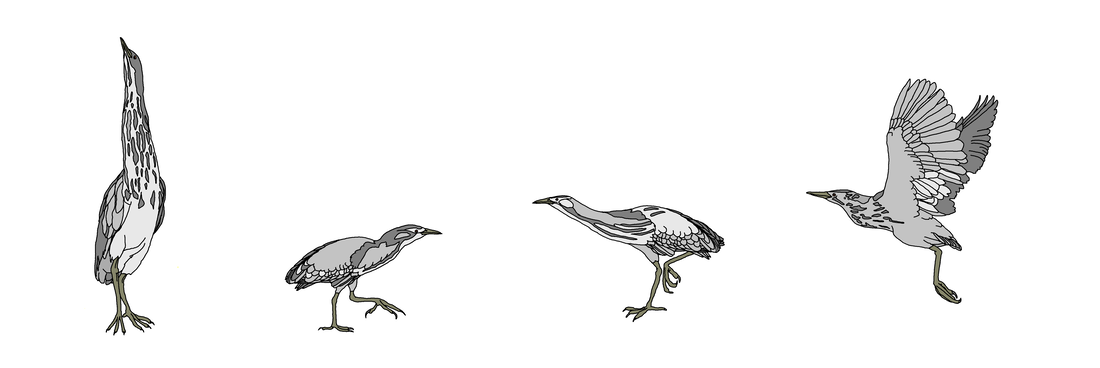

Development

The next stage, once I have investigated the structure and experimented with a few poses, is to choose the ones I like best to develop into final images.

Once I was satisfied with the outlines, I compared them to photos and made sure that the markings made sense, in a stylised fashion, then coloured them, as before, in greyscale to represent the different shades of the plumage. The final colours will be set once all the birds are complete.

And done! It’s almost midnight, time to crash, but I made it!